Leadership Assessment and Response Styles Across Cultures

Leadership Assessment and Response Styles Across Cultures

Many organizations consider leadership assessment to be a valuable component of their talent management systems for several reasons. These assessments can highlight individual strengths, identify potential areas for development, help inform selection decisions, or even support succession planning initiatives. Because leadership assessments can be leveraged in so many ways and their use can have a significant impact on personnel decisions, it is important that these assessments are used fairly and consistently across all leaders in an organization. This is especially important to consider in contexts where test-takers’ response styles may differ.

There is a growing trend across organizations to promote diversity among leadership teams. This is encouraging to see for several reasons, including the many benefits that diverse teams bring to organizations. However, with an increase in the diversity of backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives of leaders, it is important to evaluate whether the leadership assessments that get used are appropriate for all leaders. As part of this evaluation, an important place to begin is understanding whether individuals from different backgrounds respond to the assessment in the same way. The way in which a leader responds to an assessment is called their response style.

What are Response Styles

Decades of research have demonstrated that individuals often adopt response styles when completing self-report assessments. This means that they tend to display a specific pattern of responses. There are 5 common response styles that appear most frequently across different types of assessments:

- Acquiescence: a tendency to agree with most statements on the assessment, regardless of the content of the statement

- Socially Desirable: a tendency to portray oneself in an overly favorable light (i.e., exaggerate one’s strengths and minimize shortcomings)

- Extreme: a tendency to give responses at either the high or low end of the rating scale

- Midpoint: a tendency to use only the midpoint of the rating scale

- Group Reference: a tendency to compare oneself to others when making ratings

Why are Response Styles Important

Response styles are rarely intentional. In most cases, leaders are not aware that their responses follow these patterns. However, these styles can have an impact on assessment results and this is especially relevant whenever assessments are used to make comparisons across leaders. For example, if you administer an assessment to two leaders as part of a selection process and one leader has a socially desirable response style while the other has a midpoint response style, the leader who portrays themselves in a more favorable light will likely have better assessment scores than the leader who tends to portray themselves as more neutral. This means the leader with the socially desirable response style may be more likely to be selected than the leader with the midpoint response style.

Response styles are particularly concerning when there are large-scale differences in the types of response styles that some leaders use versus others. For example, if midpoint responding tends to be more prevalent among leaders from a particular cultural background and socially desirable responding is more prevalent among leaders from a different background, then there is a risk that the assessment will systematically favor leaders from one background over another. This risk means it is important to carefully examine cultural differences in response styles so that leadership assessments do not disproportionally favor leaders from one culture over another.

Response Styles Across Cultures

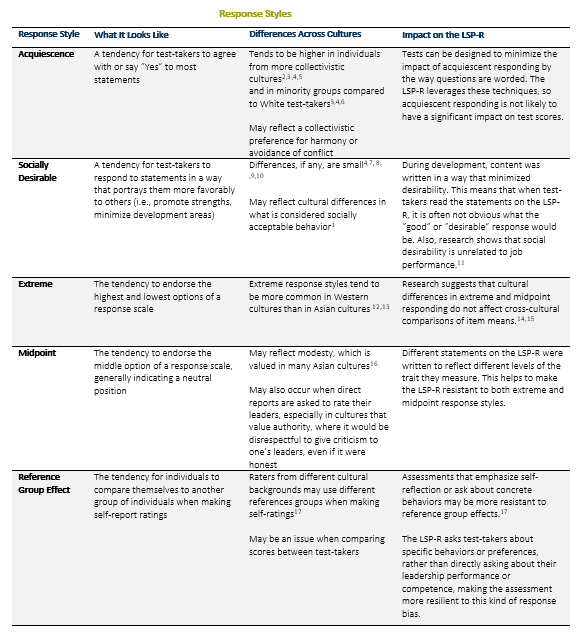

How people complete assessments may be influenced, in part, by their cultural or ethnic background. In the table below we summarize some of the most common relationships between culture and response styles that have been documented in the literature. However, it is important to be aware that the overwhelming majority of evidence suggests that if cultural differences in response styles are present, they tend to be quite small. In general, we tend to see more variability in which response styles get used within cultures than we do across different cultures [1]. This is because there are many factors beyond culture that can impact which response style gets used, including the individual’s personality and even features of the assessment itself.

How to Minimize the Impact of Response Styles on Leadership Assessments

There are several steps that test publishers can take during the development of leadership assessments to minimize the likelihood that response styles will be triggered. This is a critical step in the development of any assessment, but especially for leadership assessments that will be used with a diverse sample of leaders to inform personnel decisions.

At SIGMA, our personality-based leadership assessment, the Leadership Skills Profile – Revised (LSP-R) is a great example of such an assessment. The LSP-R is used for a variety of HR functions including selection, leadership development, and to support succession planning decisions. This is why it was so important for SIGMA to develop the LSP-R in a way that would help to minimize the impact of response styles on leaders’ assessment results. In the table below, we explain how different features of the LSP-R help to mitigate each of the different response styles. The sum of these efforts is an assessment that can be used with diverse leadership teams across a variety of contexts.

Using the LSP-R with a Diverse Sample of Leaders

The LSP-R is a valuable tool for assessing leadership competencies for a variety purposes within an organization, including selection, leader development, and succession planning. The development of the LSP-R helps to minimize the influence of response styles and results in an accurate measure of leadership potential across cultures. To learn more about how the LSP-R can be used in your organization, contact SIGMA today.

How SIGMA Can Help

If you’d like help developing your leadership competencies and using assessments like the LSP-R, check out SIGMA’s individual and group coaching, custom consulting, and succession planning services. To learn more about our solutions and how SIGMA can help your leadership team, contact us directly for more information.

[1] Bou Malham, P., & Saucier, G. (2016). The conceptual link between social desirability and cultural normativity. International Journal of Psychology, 51, 474–480.

[2] Harzing, A. (2006). Response styles in cross-national survey research: A 26-country study. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 6, 243–266.

[3] Carr, L., & Krause, N. (1978). Social status, psychiatric symptomology, and response bias. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19, 86–91.

[4] Ross, C., & Mirowsky, J. (1984). Socially-desirable response and acquiescence in a cross-cultural survey of mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 25, 189–197.

[5] Smith, P. (2004). Acquiescent response bias as an aspect of cultural communication style. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35, 50–61.

[6] Marín, G., Gamba, R. J., & Marín, B. V. (1992). Extreme response style and acquiescence among Hispanics: The role of acculturation and education. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 4, 498–509.

[7] Dunn, P., & Shome, A. (2009). Cultural crossvergence and social desirability bias: Ethical evaluations by Chinese and Canadian business students. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 527–543.

[8] Odendaal, A. (2015). Cross-cultural differences in social desirability scales: Influence of cognitive ability. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 41, 1–e13

[9] Heine, S., & Lehman, D. (1995). Social desirability among Canadian and Japanese students. The Journal of Social Psychology, 135, 777–779.

[10] Patel, C. (2003). Some cross‐cultural evidence on whistle‐blowing as an internal control mechanism. Journal of International Accounting Research, 2, 69–96.

[11] Salgado, J. F. (2005). Personality and social desirability in organizational settings: Practical implications for work and organizational psychology. Papeles del Psicologo, 26, 115-127.

[12] Dolnicar, S. & Grun, B. (2007). Cross-cultural differences in survey response patterns. International Marketing Review, 24, 127-143.

[13] Chen, C., Lee, S., & Stevenson, H. W. (1995). Response style and cross-cultural comparisons of rating scales among East Asian and North American students. Psychological Science, 6, 170–175.

[14] Zak, M., & Shigeo Takahashi, S. (1967). Cultural Influences on response style: Comparisons of Japanese and American college students, The Journal of Social Psychology, 71, 3-10.

[15] He, J., & Van De Vijver, F. (2015). Effects of a general response style on cross-cultural comparisons: Evidence from the Teaching and Learning International Survey. Public Opinion Quarterly, 79, 267–290. [1] Chun, K. T., Campbell, J. B., & Yoo, J. H. (1974). Extreme response style in cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 5, 465–479.

[16]Chun, K. T., Campbell, J. B., & Yoo, J. H. (1974). Extreme response style in cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 5, 465–479.

[17]Heine, S., Lehman, D., Peng, K., & Greenholtz, J. (2002). What’s wrong with cross-cultural comparisons of subjective Likert Scales? The reference-group effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 903–918